"Huha! Huha! Huha!" The chief of the Ngemah Longhouse, Juan, Son of Belulok, intones as he raises his gloss of Tuak, the festive rice wine. All around him the Iban men and women raise their glasses echo lng his cry. The benevolent spirits have been summoned to bear witness to the proceedings. Tonight, with the sweet and potent rice wine smoldering in

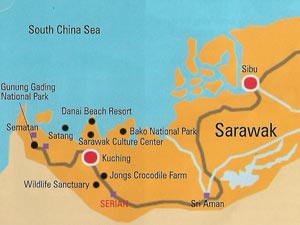

our veins, we witness the Iban ritual that invokes the protection of the guardian spirits, ensuring that no harm shall befall any of us. Deep in the rainforest of Kuching, along the churning waters of the clear Lemanak River, the proud Iban people dwell. For centuries, this has been their home. This ancient river with its spirit trees leaning vainly over their reflections, has borne the struggles of the legendary warriors and headhunters of yore. Here beneath the glorious ruby blossoms of the Ngsurai trees, where the water runs clear as molten glass, traditional Ionghouses still stand, enduring the test of time. The re-mote and secret locations of these sanc- tuaries keep the Ibaa people and their culture alive and untainted. We sit on mengkuang woven mats in the communal hall of the Ngemah Ionghouse, named after the tributary that runs from the Lemanak River. (All Ionghouses derive their names from their tributary. And it is no wonder, for it is from this source that life flows.) All around us, the jungle is alive, its rhythm gaining momentum as the night approaches. Oil lamps are lit across the communal hall, and the thirteen families that reside here are gathered to add their voices to the petition for protection, as well as to join in the festivities.

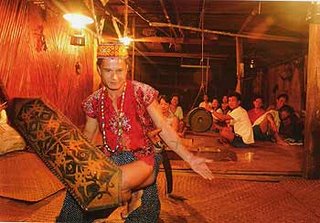

our veins, we witness the Iban ritual that invokes the protection of the guardian spirits, ensuring that no harm shall befall any of us. Deep in the rainforest of Kuching, along the churning waters of the clear Lemanak River, the proud Iban people dwell. For centuries, this has been their home. This ancient river with its spirit trees leaning vainly over their reflections, has borne the struggles of the legendary warriors and headhunters of yore. Here beneath the glorious ruby blossoms of the Ngsurai trees, where the water runs clear as molten glass, traditional Ionghouses still stand, enduring the test of time. The re-mote and secret locations of these sanc- tuaries keep the Ibaa people and their culture alive and untainted. We sit on mengkuang woven mats in the communal hall of the Ngemah Ionghouse, named after the tributary that runs from the Lemanak River. (All Ionghouses derive their names from their tributary. And it is no wonder, for it is from this source that life flows.) All around us, the jungle is alive, its rhythm gaining momentum as the night approaches. Oil lamps are lit across the communal hall, and the thirteen families that reside here are gathered to add their voices to the petition for protection, as well as to join in the festivities. The haunting melody of the Ngkrumong fills the hall. The poignant tones produced by these small gongs is punctuated by the feverish beat of the Tawak and Bendai, brass gongs customarily used in tribal ceremonies, to drown out the sounds wrought by bad omen birds, As the rhythm increases, a sinewy Iban man, swathed in a dark blue loin cloth with the feathers of the pheasant and hornbill adorning his hair, and bearing the ornately carved oblong wooden shield and parang of the warrior, begins his dance. Bathed in the warm light of the oil lamps, his movements are strong and firm. Colourful beads swing around his neck as he lets out a bird-Pke cry, and swivels into a near squatting position, his thighs bulging with muscle. He strikes dramatically Iow stances and skillfully maneuvers his shield around him in time to the pulsing beat of the gendang. The warrior looks up and down, his arms taking on the movement of flapping wings, bringing to life the rhinocerous hornbill in his every step.

The haunting melody of the Ngkrumong fills the hall. The poignant tones produced by these small gongs is punctuated by the feverish beat of the Tawak and Bendai, brass gongs customarily used in tribal ceremonies, to drown out the sounds wrought by bad omen birds, As the rhythm increases, a sinewy Iban man, swathed in a dark blue loin cloth with the feathers of the pheasant and hornbill adorning his hair, and bearing the ornately carved oblong wooden shield and parang of the warrior, begins his dance. Bathed in the warm light of the oil lamps, his movements are strong and firm. Colourful beads swing around his neck as he lets out a bird-Pke cry, and swivels into a near squatting position, his thighs bulging with muscle. He strikes dramatically Iow stances and skillfully maneuvers his shield around him in time to the pulsing beat of the gendang. The warrior looks up and down, his arms taking on the movement of flapping wings, bringing to life the rhinocerous hornbill in his every step.As the rhinoceros hornbill shrieks for the last time, the melody dies down and the dance of the pheasant commences. This is performed by a barefoot Iban woman, attired in an exotic tribal dress. On her head, she wears the carved sugu comb topped with a delicate tiara. As she dips gracefully, moving her hands in a soothing motion, the brass bells that encircle her ankles clink and jingle adding to the alIure of the dance. The dances of the hornbill and pheasant are performed by another Iba, man and woman. Finally, the dancers come together and begin dancing in a circle, twirling, a blur of brilliant colors and feathers. The Ngkrumong is hushed, the beat of the gendang, tawak and bendai begins to slow down, and the ceremony is over for tonight.

With rice wine spilling over onto the finery woven mats, we get ready for the night. Whilat the families disappear into

their rooms, we sleep in the communal hall, called the 'ruai', where sheer canopies of mesquite nets have been erected over soft mattresses, the lamps illuminating these most personal of spaces, Perhaps, an explnation is necessary far this statement. I say 'most personal' because, the way of life of the Iban people seems so open, personal space is limited. Everthing seems to be shared, The only space that seems private is within the confines of the mosquito net. To fully understand this, one has to observe the amazing structure of die tonghesso. The amazing longhouse, like all others, is accessed by climbing a flight of steep and narrow steps carved from the bark of a tree. The first step on this unique stairway has a tail carved into it symbolizing the bottom, whilst at the peak, a face peeks somewhat eerily, Upon passing this threshold, one enters the realm of the longhouse. A long patio of split bamboo rolls along, extending to the very end of the house. This area is used for drying produce, clothes or simply for enjoying the light evening breeze, with the full view of the steep rice hills rising like brilliant jade mountains in the back- ground. Entering the wooden longhouse from any of the numerous doorways, one stumbles upon the 'mai' where many a languid afternoon is spent sheltering from the rays of the sun, weaving rattan bas kets, sharpening toeIs, mending fishing nets or simply snoozing in this peculiar sphere, the paragon of private publicness. Here neighbors are family. The close proximity that would have most families flying at each other's throats creates a strong bond here, and squabbles are hardly heard of. In light of such clustered sharing, it should net come as much of a surprise to note that the 'bilik' or family room affords as much privacy as the shrubs by the riverbank. Consisting of just one living area, where the whole family resides, this space often hosts up to three generations at a time, When a man and woman are married, they join the man's parents in their quarters. In this space their very awn family will take root and grow too, an ancestral room for the many generations of apai(fathers) and inai(mothers) who will live, love and pass on to the next world.

their rooms, we sleep in the communal hall, called the 'ruai', where sheer canopies of mesquite nets have been erected over soft mattresses, the lamps illuminating these most personal of spaces, Perhaps, an explnation is necessary far this statement. I say 'most personal' because, the way of life of the Iban people seems so open, personal space is limited. Everthing seems to be shared, The only space that seems private is within the confines of the mosquito net. To fully understand this, one has to observe the amazing structure of die tonghesso. The amazing longhouse, like all others, is accessed by climbing a flight of steep and narrow steps carved from the bark of a tree. The first step on this unique stairway has a tail carved into it symbolizing the bottom, whilst at the peak, a face peeks somewhat eerily, Upon passing this threshold, one enters the realm of the longhouse. A long patio of split bamboo rolls along, extending to the very end of the house. This area is used for drying produce, clothes or simply for enjoying the light evening breeze, with the full view of the steep rice hills rising like brilliant jade mountains in the back- ground. Entering the wooden longhouse from any of the numerous doorways, one stumbles upon the 'mai' where many a languid afternoon is spent sheltering from the rays of the sun, weaving rattan bas kets, sharpening toeIs, mending fishing nets or simply snoozing in this peculiar sphere, the paragon of private publicness. Here neighbors are family. The close proximity that would have most families flying at each other's throats creates a strong bond here, and squabbles are hardly heard of. In light of such clustered sharing, it should net come as much of a surprise to note that the 'bilik' or family room affords as much privacy as the shrubs by the riverbank. Consisting of just one living area, where the whole family resides, this space often hosts up to three generations at a time, When a man and woman are married, they join the man's parents in their quarters. In this space their very awn family will take root and grow too, an ancestral room for the many generations of apai(fathers) and inai(mothers) who will live, love and pass on to the next world. Discussion of privacy and matrimonial affairs is net complete without mention of the old courtship custom or 'ngayap', which has ceased to be practiced today for various reasons. It seems, in the old days, when toiling in the fie/ds left little time for the young to socialize, it was acceptable for the suitor to visit his intended in her family room at night, And so, in the darkness, accompanied by the busy buzzing of the nocturnal insects and prob- ably the rapid thumping of his head, the earnest suitor would steal into the girl's family 'biIik' and after a brief introduction, enter her mosquito net to get better acquainted. How cozy! Next to her net, the girlwould keep an oil lamp burning. Should the girl wish to reject the advances, she would relight the oil lamp, and the suitor would disappear into the night. Shouldshe allow the lamp to go out, this would signify her acceptance. It was impera-five that this nocturnal visit proceed for three consecutive nights, in order for the couple to become adequately acquainted to make a decision regarding marriage. During this time, the couple would only be permitted to converse, nothing else. But although this tropical paradise seems like the Garden of Eden, this is not utopia, and ieevitahtv an overtg amorous suitor would have just a little more than talking on his mind. After all, the mosquito net rouses strange feelings. And so, in light of decaying chivalry, this charming practice has been abandoned.

Discussion of privacy and matrimonial affairs is net complete without mention of the old courtship custom or 'ngayap', which has ceased to be practiced today for various reasons. It seems, in the old days, when toiling in the fie/ds left little time for the young to socialize, it was acceptable for the suitor to visit his intended in her family room at night, And so, in the darkness, accompanied by the busy buzzing of the nocturnal insects and prob- ably the rapid thumping of his head, the earnest suitor would steal into the girl's family 'biIik' and after a brief introduction, enter her mosquito net to get better acquainted. How cozy! Next to her net, the girlwould keep an oil lamp burning. Should the girl wish to reject the advances, she would relight the oil lamp, and the suitor would disappear into the night. Shouldshe allow the lamp to go out, this would signify her acceptance. It was impera-five that this nocturnal visit proceed for three consecutive nights, in order for the couple to become adequately acquainted to make a decision regarding marriage. During this time, the couple would only be permitted to converse, nothing else. But although this tropical paradise seems like the Garden of Eden, this is not utopia, and ieevitahtv an overtg amorous suitor would have just a little more than talking on his mind. After all, the mosquito net rouses strange feelings. And so, in light of decaying chivalry, this charming practice has been abandoned.It seems that women who sleep past 7.0Oam, are considered lazy, and therefore undesirable. But, what about holidays or weekends? In the Ionghouse, time as we know it holds no significance. They are not bound by days on a calendar, but by the moon, the rain, the changing of the seasons that leads up to the harvest. Everyday is a day of work, and work is a way of life.

No comments:

Post a Comment