The Ibans are a branch of the Dayak peoples of Borneo. They were formerly known during the colonial period by the British as Sea Dayaks. Ibans were renowned for practising headhunting and tribal/territorial expansion. A long time ago, being a very strong and successful warring tribe, the Ibans were a very feared tribe in Borneo. They speak the Iban Language.

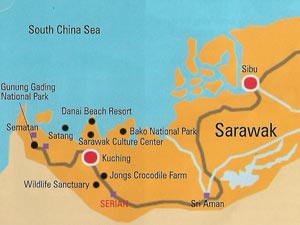

Today, the days of headhunting and piracy are long gone and in has come the modern era of globalization and technology for the Ibans. The Iban population is concentrated in Sarawak, Brunei, in the West Kalimantan region of Indonesia. They live inlonghouses called rumah panjai or rumah panjang Most of the Iban longhouses are equipped with modern facilities such as electricity and water supply and other facilities such as (tar sealed) roads, telephone lines and the internet. Younger Ibans are mostly found in urban areas and visit their hometowns during the holidays. The Ibans today are becoming increasingly urbanised while (surprisingly) retaining most of their traditional heritage and culture.

Iban History

The origin of the name Iban is a mystery, although many theories exist. During the British colonial era, the Ibans were called Sea Dayaks. Some believe that the word Iban was an ancient original Iban word for People or man. The modern-day Iban word for people or man is mensia, a slightly modified Malay loan word of the same meaning (manusia).

The Ibans were the original inhabitants of Borneo Island. Like the other Dayak tribes, they were originally farmers, hunters, and gatherers. Not much is known about Iban people before the arrival of the Western expeditions to Asia. Nothing was ever recorded by any voyagers about them.

The Ibans were unfortunately branded for being pioneers of headhunting. Headhunting among the Ibans is believed to have started when the lands occupied by the Ibans became over-populated. In those days, before the arrival of western civilization, intruding on lands belonging to other tribes resulted in death. Confrontation was the only way of survival.

In those days, the way of war was the only way that any Dayak tribe could achieve prosperity and fortune. Dayak warfare was brutal and bloody, to the point of ethnic cleansing. Many extinct tribes, such as the Seru and Bliun, are believed to have been assimilated or wiped out by the Ibans. Tribes like theBukitan, who were the original inhabitants of Saribas, are believed to have been assimilated or forced northwards as far as Bintulu by the Ibans. The Ukits were also believed to have been nearly wiped out by the Ibans.

The Ibans started moving to areas in what is today's Sarawak around the 15th century. After an initial phase of colonising and settling the river valleys, displacing or absorbing the local tribes, a phase of internecine warfare began. Local leaders were forced to resist the tax collectors of the sultans of Brunei. At the same time, Malay influence was felt, and Iban leaders began to be known by Malay titles such as Datu (Datuk), Nakhoda and Orang Kaya.

In later years, the Iban encountered the Bajau and Illanun, coming in galleys from the Philippines. These were sea-faring tribes who came plundering throughout Borneo. However, the Ibans feared no tribe, and fought the Bajaus and Illanuns. One famous Iban legendary figure known as Lebor Menoa from Entanak, near modern-day Betong, fought and successfully defeated the Bajaus and Illanuns. It is likely that the Ibans learned sea-faring skills from the Bajau and the Illanun, using these skills to plunder other tribes living in coastal areas, such as the Melanaus and the Selakos. This is evident with the existence of the seldom-used Iban boat with sail, called the bandung. This may also be one of the reasons James Brooke, who arrived in Sarawak around 1838, called the Ibans Sea Dayaks. For more than a century, the Ibans were known as Sea Dayaks to Westerners.

Religion, Culture and Festivals

The Ibans were traditionally animist, although the majority are now Christian, some of them Muslim and many continue to observe both Christian and traditional ceremonies, particularly during marriages or festivals.

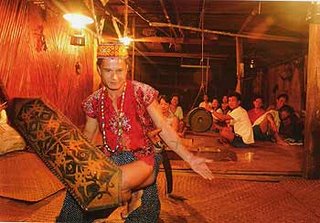

Significant festivals include the rice harvesting festival Gawai Dayak, the main festival for the Ibans. Other festivals include the bird festival Gawai Burong and the spirit festival Gawai Antu. The Gawai Dayak festival is celebrated every year on the 1st of June, at the end of the harvest season, to worship the Lord Sempulang Gana. On this day, the Ibans get together to celebrate, often visiting each other. The Iban traditional dance, the ngajat, is performed accompanied by the taboh and gendang, the Ibans' traditional music. Pua Kumbu, the Iban traditional cloth, is used to decorate houses. Tuak, which is originally made of rice, is a wine used to serve guests. Nowadays, there are various kinds of tuak, made with rice alternatives such as sugar cane, ginger and corn.

The Gawai Burong (the bird festival) is held in honour of the War God, Singalang Burong. The name Singalang Burong literally means "Singalang the Bird". This festival is initiated by a notable individual from time to time and hosted by individual longhouses. The Gawai Burong originally honoured warriors, but during more peaceful times evolved into a healing ceremony. The recitation of pantun (traditional chants by poets) is a particularly important aspect of the festival.

For the majority of Ibans who are Christians, some Chrisitian festivals such as Christmas, Good Friday, Easter, and other Christian festivals are also celebrated. Most Ibans are devout Christians and follow the Christian faith strictly.

Despite the difference in faiths, Ibans of different faiths do help each other during Gawais and Christmas. Differences in faith is never a problem in the Iban community. The Ibans believe in helping and having fun together. This is ironic for a tribe who once waged war with others due to differences.

.jpg)